The literary world was rocked by the astonishing discovery of the Nag Hammadi library, a truly rare archaeological find that occurs only once in a century. This extraordinary collection consists of various lost Gnostic scripts, believed to have been written in Coptic during the 4th century. At that time, the Coptic language was widely renowned as one of the most prominent ancient Egyptian languages. Among the intriguing texts found within the Nag Hammadi codices is the Gospel of Thomas, which owes its present completeness to the unearthing of these ancient manuscripts. Currently, these invaluable treasures are safely housed at the esteemed Coptic Museum in Cairo, Egypt.

How were the Nag Hammadi scripts discovered?

In the month of December in 1945, near the town of Nag Hammadi, Egypt, two Egyptian villagers embarked on a search for fertiliser close to a cliff. Little did they know that their excavation would lead to an astonishing discovery. As they dug deeper, they stumbled upon a collection of jars hidden within the cliff. These jars contained an incredible treasure – 13 books, carefully concealed by Christians approximately 1600 years ago.

What makes this find truly remarkable is the fact that within these 13 books, a total of 57 texts were uncovered. Some of these texts even had duplicate copies, offering a truly fascinating insight into the ancient Christian world. What’s even more intriguing is that some of these scripts were completely unknown to us until now.

The unearthing of the Nag Hammadi scripts has not only shed light on the rich history of Christianity, but it has also sparked a sense of wonder and curiosity among scholars and enthusiasts alike. These invaluable texts provide a glimpse into a world long gone, offering us a deeper understanding of the beliefs and practices of early Christians.

The discovery of these ancient manuscripts serves as a testament to the power of archaeological exploration and the importance of preserving our past. It is through such remarkable finds that we can continue to unravel the mysteries of our history, gaining insights into the diverse cultures and ideologies that have shaped our world.

Why is the Discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library so Important?

The discovery of the Nag Hammadi Library has provided us with a remarkable opportunity to explore the vast diversity of Christian texts and belief systems that existed in the ancient world. This groundbreaking find has significantly contributed to our understanding of the development and evolution of the Christian faith. In essence, it has enriched our data and allowed us to make meaningful comparisons between different Christian groups and their relationship to the New Testament scripts.

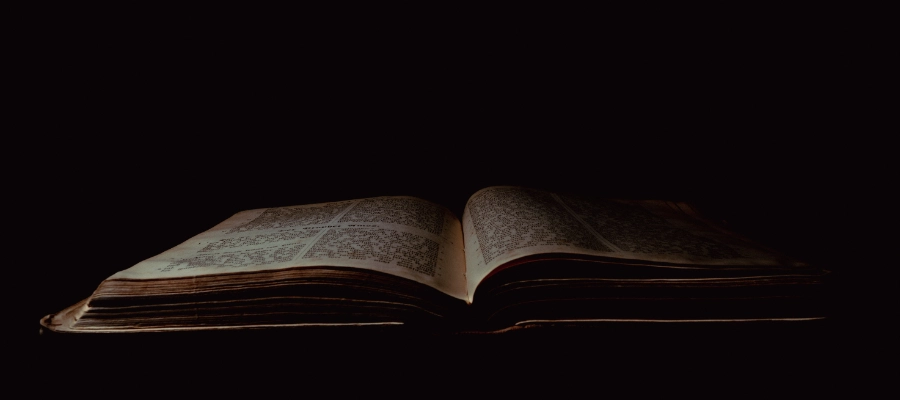

One noteworthy aspect of the Nag Hammadi texts is their dating, which predates the canonical texts. This indicates that these writings offer valuable insights into the early Christian community and it’s theological perspectives. The Nag Hammadi writings, while primarily focusing on aesthetics and theory, shed light on the intellectual and spiritual currents of the time.

The significance of the Nag Hammadi discovery cannot be overstated. It has expanded our knowledge of early Christianity and revealed the remarkable diversity of beliefs within the faith. This finding has opened up new avenues for research and deepened our understanding of the complex tapestry of Christian thought in the ancient world.

The Nag Hammadi Library is a treasure trove of ancient Christian texts that has revolutionised our understanding of early Christianity. Its discovery has allowed us to delve into the rich tapestry of beliefs within the faith and gain invaluable insights into the development of Christian thought. This finding is undoubtedly one of the most important archaeological and academic discoveries in the field of religious studies.

Unveiling the Enigmatic Figures behind the Buried Jars

The individuals associated with the concealed jars have remained shrouded in mystery. As scholars speculate, these enigmatic figures were likely affiliated with an educational institution or monastic community. Their profound connection to Christianity indicates that they were probably Christian monks who sought to safeguard their sacred texts. Concealing these manuscripts in jars served as a precautionary measure to avoid accusations of heresy amidst an emerging threat faced by the dominating Christian community at this time.

The reason behind the burial of the scripts in the sands of Egypt is a subject of speculation. It is believed that the Nag Hammadi documents were hidden, possibly by monks, in order to protect them from being destroyed by those who sought to eradicate heretical writings. In 367, the bishop of Alexandria, Aphenisus, expressed his disapproval of people reading heretical texts and published a list of sanctioned books, which included the same 27 books that form the New Testament canon today.

Scholars have determined that the Nag Hammadi texts date back to the same period when Aphenisus was active. This conclusion was reached by examining the interior of the leather cover of Codex 5, which was reinforced with a layer of papyrus that could be carbon-dated.

Critics have raised objections to this theory, questioning the true extent of Aphenisus’s power. They argue that during the time period in question, bishops held less authority compared to their counterparts in the Middle Ages. As a result, it remains uncertain whether Aphenisus played a significant role in shaping the power dynamics of that era. Regrettably, the exact truth may forever elude us.

The act of hiding these texts indicates that the monks and Christians involved were concerned about being accused of heresy. The Christian community faced a new threat during that time, prompting them to safeguard their sacred texts from the orthodox church. It is therefore believed that a monastic order or perhaps a school for readers may have been responsible for hiding the texts, as previously suggested.

The burial of the Nag Hammadi scripts in Egypt’s sands was likely motivated by a desire to protect them from destruction and avoid accusations of heresy. The discovery of these texts provides valuable insights into the history and beliefs of early Christians.

We delve into the evidence supporting the theory that these hidden texts were the work of monastic readers.

1. The Hidden Texts: A Symbol of Caution

The deliberate act of hiding the texts serves as a testament to the fear and apprehension felt by these monks and Christians. Their desire to avoid scrutiny from the orthodox church suggests a clandestine operation aimed at safeguarding their beliefs and teachings.

2. Monastic Lifestyle and Knowledge

Renowned for their dedication to learning and intellectual pursuits, monastic communities align with the act of preserving and concealing these texts. It reflects their tradition of safeguarding knowledge and promoting spiritual enlightenment.

3. Historical Context: Emerging Threats

During the time when these texts were hidden, the Christian community faced new and potentially dangerous challenges. It is plausible that the monks sought to protect their sacred texts from external threats that could have compromised their religious practices and beliefs.

4. Proximity to the Pochomian Monastery

The discovery site’s close proximity to the Pochomian monastery, a mere 5 km away, raises the possibility of a monk connection. The geographical relationship between the jars and the monastery suggests a potential affiliation between the two.

5. Christian Monks and the Nag Hammadi Literature

The Nag Hammadi literature was found near tombs known to have been utilized by Christian monks. This conclusion is reinforced by the presence of Christian graffiti on the walls of these tombs. These indications strongly suggest that the monks were connected to the burial of the jars.

6. Meticulous Preservation Method

The meticulous preservation of the texts in jars further supports the involvement of monastic readers. This method of storage reflects their meticulousness and emphasizes the value they placed on these manuscripts.

7. Coptic Language and Monastic Involvement

The use of Coptic language in the texts, instead of Greek, provides further insight into the possible involvement of monks. During the relevant time period, Coptic was the prevailing language among most Egyptian monks. This linguistic choice further supports the notion of a monastic presence.

8. Correspondence Fragments

The fragments of papyrus used to cover the book covers were discovered to be correspondences between monks. This discovery adds another layer of evidence to the monk theory, implying that the individuals responsible for hiding the scripts were engaged in communication with one another.

While the specifics of these monastic readers remain elusive, the evidence strongly suggests their involvement in the concealment and preservation of these texts. As we piece together the clues left behind, we gain a deeper understanding of the motivations and fears that compelled these individuals to act. By unearthing the identity of these mysterious figures, we can gain valuable insights into the historical context of their time and the challenges faced by the Christian community.

The cumulative evidence points towards the involvement of monks in the burial of the jars. The proximity to the Pochomian monastery, the presence of Christian graffiti near the discovery site, the use of Coptic language in the texts, and the correspondence fragments all contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the enigmatic figures behind the hidden scripts.

When was the Nag Hammadi text composed?

According to scholars, it is believed that these documents were initially translated into Greek and subsequently translated into Coptic. Based on current estimations, these texts were likely composed during the 2nd and 3rd century AD.

What books have we found at Nag Hammadi?

In this comprehensive analysis, I will meticulously present an organized list of scripts, precisely categorized according to the classifications established by scholars. The scripts included in this compilation were previously unknown to us or lacked any existing copies. The magnitude of this discovery is truly remarkable and awe-inspiring.

Prior to this breakthrough, our understanding of early Christian writings was primarily reliant on the accounts of the Christian Church, such as Irenaeus or Origen, who held strong biases against alternative Christianities, often labeling them as heretical.

Considering the supplementary objectives and instructions, I aim to deliver this information in a clear and knowledgeable manner, while also incorporating a personal touch. Each sentence will be crafted to captivate readers, ensuring an engaging reading experience.

Book (Codex) 1

- The Prayer of Paul (never heard before)

- The Secret book of James (never heard before)

- The Gospel of Truth (we knew from Irenaeus but we haven’t had a chance to read it before)

- Treatise on Resurrection (never heard before)

- Tripartite Tractate (never heard before)

If you think that was amazing, wait it will get even better…

Book (Codex) 2

- The Secret Book of John (Apocrypha of John)

- The Gospel of Thomas (I have written a comprehensive blog post about it here)

- The Gospel of Philipp

- The Nature of the Rulers (never heard before)

- Origen of the World (this is not the original title – scholars gave it this name now)

- Exegesis of the soul

- Book of Thomas (the contender)

Book (Codex) 3

- Again, the Secret Book of John (the book of Gnostic Christians)

- The holy book of the Great Invisible Spirit (the Egyptian Gospel)

- Eugnostus the Blessed

- Wisdom of Jesus Christ

- The Dialog of the Saviour

Book (Codex) 4

- The Secret Book of John (this is the second time the book was included)

- The second copy of The holy book of the Great Invisible Spirit

Book (Codex) 5

- Eugnostus the Blessed (the second time)

- Apocalypse of Paul (never heard before)

- First Apocalypse of James

- Second Apocalypse of James

- Apocalypse of Adam

Book (Codex) 6

- The Acts of Peter and the Twelve Apostles (previously unknown to us)

- Thunder (never heard before)

- Authoritative Discourse (never heard before)

- Concept of our Great Power (never heard before)

- Excerpt of Plato’s Republic (we knew about that but we didn’t know it was excerpted)

- Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth (an unknown hermetic text)

- The Prayer of Thanksgiving (a previous known hermetic text)

- Excerpt from Perfect Discourse (we had that before in a Latin translation)

- Asclepius

Book (Codex) 7

- Paraphrase of Shem (never heard before)

- Second Treatise of Great Seth (a masterpiece we haven’t heard before)

- Apocalypse of Peter (never heard before)

- Teachings of Silvanus

- Three Steles of Seth

Book (Codex) 8

- Zostrianos

- Letter of Peter to Philip

Book (Codex) 9

- Melchizedek

- Thought of Norea (a female matriarch)

- Testimony of Truth

Book (Codex) 10

- book 10 contains only Marsanes and badly damaged

Book (Codex) 11

- Interpretation of Knowledge

- Valentinian Exposition

- On Anointing

- on Baptism

- On the Eucharist

- Allogenes

- Hypsiphrone (another female entity)

Book (Codex) 12

- Sentences of Sextus

- Gospel of Truth (second copy)

- Fragments

Book (Codex) 13

- Three Forms of First Thought (Trimorphic Protennoia)

- On the Origin of the World

Summary

The Nag Hammadi discovery is a significant find that includes various Christian theologies written centuries before. The Gnostic gospels, previously only found in Coptic translations, have now been discovered in their original Greek and Aramaic languages. Additionally, this collection contains writings from female Gnostics, new insights on baptism and the Eucharist, and a diverse range of texts on topics such as the origins of the world. These texts differ greatly from one another, making this finding truly unique and valuable.

FAQ:

Why is the Nag Hammadi library so important?

It revolutionised our understanding of Christianity in the first couple of centuries of its beginning and let us view deep into the variety of theological thinking of different Christian nominations.

What do the Nag Hammadi texts say?

A simple answer is impossible as the Nag Hammadi text contains 13 books with different theological views.

Where are the Nag Hammadi scrolls kept?

It is kept at the Coptic Museum in Cairo, Egypt.

Is the Gospel of Thomas in the Nag Hammadi?

Yes, it is part of the Book (Codex) 2

What is wrong with the Gnostic Gospels?

Nothing is wrong with it, it is just a different take on Christianity that developed over time.

How old are the Nag Hammadi Scriptures?

Nothing is wrong with it, it is just a different take on Christianity that developed over time.